How Was Value Added To Your Learning Process By Participating In The Metacognitive Forums

Metacognition

Cite this guide: Chick, N. (2013). Metacognition. Vanderbilt University Heart for Teaching. Retrieved [todaysdate] from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/metacognition/.

Thinking well-nigh Ane'due south Thinking | Putting Metacognition into Exercise

Thinking almost Ane'southward Thinking

Metacognition is, put simply, thinking about ane'south thinking. More precisely, it refers to the processes used to programme, monitor, and assess one'south agreement and performance. Metacognition includes a critical awareness of a) one'south thinking and learning and b) oneself as a thinker and learner.

Initially studied for its development in young children (Bakery & Brown, 1984; Flavell, 1985), researchers soon began to expect at how experts brandish metacognitive thinking and how, then, these thought processes can be taught to novices to improve their learning (Hatano & Inagaki, 1986). In How People Larn, the National Academy of Sciences' synthesis of decades of research on the science of learning, i of the three key findings of this piece of work is the effectiveness of a "'metacognitive' arroyo to instruction" (Bransford, Chocolate-brown, & Cocking, 2000, p. eighteen).

Metacognitive practices increase students' abilities to transfer or arrange their learning to new contexts and tasks (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, p. 12; Palincsar & Chocolate-brown, 1984; Scardamalia et al., 1984; Schoenfeld, 1983, 1985, 1991). They do this by gaining a level of awareness in a higher place the subject matter: they also think nigh the tasks and contexts of different learning situations and themselves as learners in these dissimilar contexts. When Pintrich (2002) asserts that "Students who know about the different kinds of strategies for learning, thinking, and problem solving volition be more likely to apply them" (p. 222), observe the students must "know about" these strategies, not simply exercise them. As Zohar and David (2009) explicate, at that place must exist a "conscious meta-strategic level of H[igher] O[rder] T[hinking]" (p. 179).

Metacognitive practices help students become enlightened of their strengths and weaknesses as learners, writers, readers, examination-takers, group members, etc. A primal chemical element is recognizing the limit of one's noesis or ability and and then figuring out how to expand that knowledge or extend the ability. Those who know their strengths and weaknesses in these areas will exist more probable to "actively monitor their learning strategies and resources and assess their readiness for detail tasks and performances" (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, p. 67).

The absence of metacognition connects to the research past Dunning, Johnson, Ehrlinger, and Kruger on "Why People Fail to Recognize Their Own Incompetence" (2003). They found that "people tend to be blissfully unaware of their incompetence," lacking "insight about deficiencies in their intellectual and social skills." They identified this pattern across domains—from test-taking, writing grammatically, thinking logically, to recognizing humor, to hunters' noesis nearly firearms and medical lab technicians' noesis of medical terminology and trouble-solving skills (p. 83-84). In short, "if people lack the skills to produce right answers, they are also cursed with an inability to know when their answers, or anyone else's, are right or wrong" (p. 85). This inquiry suggests that increased metacognitive abilities—to larn specific (and correct) skills, how to recognize them, and how to practice them—is needed in many contexts.

Putting Metacognition into Practice

In "Promoting Student Metacognition," Tanner (2012) offers a scattering of specific activities for biology classes, but they can be adapted to any bailiwick. She kickoff describes four assignments for explicit pedagogy (p. 116):

- Preassessments—Encouraging Students to Examine Their Current Thinking: "What do I already know near this topic that could guide my learning?"

- The Muddiest Bespeak—Giving Students Practise in Identifying Confusions: "What was well-nigh disruptive to me about the textile explored in class today?"

- Retrospective Postassessments—Pushing Students to Recognize Conceptual Change: "Before this course, I thought evolution was… Now I call back that evolution is …." or "How is my thinking changing (or not changing) over time?"

- Reflective Journals—Providing a Forum in Which Students Monitor Their Own Thinking: "What about my examination preparation worked well that I should think to do adjacent fourth dimension? What did not work so well that I should non do next time or that I should change?"

Next are recommendations for developing a "classroom civilization grounded in metacognition" (p. 116-118):

- Giving Students License to Identify Confusions within the Classroom Culture: ask students what they notice confusing, acknowledge the difficulties

- Integrating Reflection into Credited Course Piece of work: integrate short reflection (oral or written) that ask students what they institute challenging or what questions arose during an assignment/exam/project

- Metacognitive Modeling by the Instructor for Students: model the thinking processes involved in your field and sought in your grade past beingness explicit about "how y'all start, how you decide what to do beginning and so next, how you lot check your piece of work, how you know when you are done" (p. 118)

To facilitate these activities, she also offers three useful tables:

- Questions for students to ask themselves every bit they plan, monitor, and evaluate their thinking within 4 learning contexts—in grade, assignments, quizzes/exams, and the grade equally a whole (p. 115)

- Prompts for integrating metacognition into discussions of pairs during clicker activities, assignments, and quiz or exam preparation (p. 117)

- Questions to assist kinesthesia metacognitively assess their ain didactics (p. 119)

Weimer'due south "Deep Learning vs. Surface Learning: Getting Students to Empathize the Departure" (2012) offers additional recommendations for developing students' metacognitive sensation and improvement of their study skills:

"[I]t is terribly important that in explicit and concerted ways nosotros make students aware of themselves as learners. We must regularly ask, not but 'What are y'all learning?' but 'How are y'all learning?' We must face up them with the effectiveness (more ofttimes ineffectiveness) of their approaches. Nosotros must offer alternatives and and so challenge students to test the efficacy of those approaches. " (emphasis added)

She points to a tool adult past Stanger-Hall (2012, p. 297) for her students to identify their study strategies, which she divided into "cognitively passive" ("I previewed the reading before class," "I came to class," "I read the assigned text," "I highlighted the text," et al) and "cognitively agile study behaviors" ("I asked myself: 'How does it work?' and 'Why does it work this fashion?'" "I wrote my own report questions," "I fit all the facts into a bigger picture," "I closed my notes and tested how much I remembered," et al). The specific focus of Stanger-Hall's written report is tangential to this discussion,ane but imagine giving students lists like hers adjusted to your course then, after a major assignment, having students talk over which ones worked and which types of behaviors led to college grades. Even further, follow Lovett's advice (2013) past assigning "exam wrappers," which include students reflecting on their previous examination-training strategies, assessing those strategies and and then looking alee to the next exam, and writing an action plan for a revised approach to studying. A common assignment in English limerick courses is the cocky-cess essay in which students apply course criteria to articulate their strengths and weaknesses inside single papers or over the grade of the semester. These activities can be adapted to assignments other than exams or essays, such as projects, speeches, discussions, and the like.

As these examples illustrate, for students to become more metacognitive, they must be taught the concept and its linguistic communication explicitly (Pintrich, 2002; Tanner, 2012), though not in a content-delivery model (merely a reading or a lecture) and non in one lesson. Instead, the explicit educational activity should be "designed according to a knowledge construction arroyo," or students need to recognize, assess, and connect new skills to old ones, "and it needs to have place over an extended period of time" (Zohar & David, p. 187). This kind of explicit instruction will help students expand or replace existing learning strategies with new and more constructive ones, give students a way to talk about learning and thinking, compare strategies with their classmates' and make more than informed choices, and return learning "less opaque to students, rather than being something that happens mysteriously or that some students 'get' and larn and others struggle and don't learn" (Pintrich, 2002, p. 223).

Metacognition instruction should likewise exist embedded with the content and activities most which students are thinking. Why? Metacognition is "non generic" (Bransford, Brownish, & Cocking, p. 19) but instead is most effective when it is adapted to reflect the specific learning contexts of a specific topic, course, or discipline (Zohar & David, 2009). In explicitly connecting a learning context to its relevant processes, learners volition be more able to adapt strategies to new contexts, rather than assume that learning is the aforementioned everywhere and every time. For instance, students' abilities to read disciplinary texts in subject-advisable ways would also  benefit from metacognitive practice. A literature professor may read a passage of a novel aloud in class, while also talking about what she'south thinking as she reads: how she makes sense of specific words and phrases, what connections she makes, how she approaches difficult passages, etc. This kind of modeling is a good practice in metacognition education, as suggested by Tanner higher up. Concepción's "Reading Philosophy with Background Knowledge and Metacognition" (2004) includes his detailed "How to Read Philosophy" handout (pp. 358-367), which includes the following components:

benefit from metacognitive practice. A literature professor may read a passage of a novel aloud in class, while also talking about what she'south thinking as she reads: how she makes sense of specific words and phrases, what connections she makes, how she approaches difficult passages, etc. This kind of modeling is a good practice in metacognition education, as suggested by Tanner higher up. Concepción's "Reading Philosophy with Background Knowledge and Metacognition" (2004) includes his detailed "How to Read Philosophy" handout (pp. 358-367), which includes the following components:

- What to Expect (when reading philosophy)

- The Ultimate Goal (of reading philosophy)

- Basic Good Reading Behaviors

- Important Background Data, or field of study- and class-specific reading practices, such as "reading for enlightenment" rather than data, and "problem-based classes" rather than historical or figure-based classes

- A 3-Part Reading Process (pre-reading, understanding, and evaluating)

- Flagging, or annotating the reading

- Linear vs. Dialogical Writing (Philosophical writing is rarely straightforward but instead "a monologue that contains a dialogue" [p. 365].)

What would such a handout look like for your subject area?

Students tin fifty-fifty be metacognitively prepared (and then gear up themselves) for the overarching learning experiences expected in specific contexts. Salvatori and Donahue's The Elements (and Pleasures) of Difficulty (2004) encourages students to embrace difficult texts (and tasks) every bit part of deep learning, rather than an obstacle. Their "difficulty paper" assignment helps students reverberate on and articulate the nature of the difficulty and piece of work through their responses to it (p. ix). Similarly, in courses with sensitive subject matter, a different kind of learning occurs, one that involves complex emotional responses. In "Learning from Their Own Learning: How Metacognitive and Meta-affective Reflections Enhance Learning in Race-Related Courses" (Chick, Karis, & Kernahan, 2009), students were informed nearly the common reactions to learning about racial inequality (Helms, 1995; Adams, Bell, & Griffin, 1997; come across student handout, Chick, Karis, & Kernahan, p. 23-24) and and so regularly wrote virtually their cognitive and affective responses to specific racialized situations. The students with the near adult metacognitive and meta-affective practices at the end of the semester were able to "clear the obstacles and move abroad from" oversimplified thinking almost race and racism "to places of greater questioning, acknowledging the complexities of identity, and redefining the earth in racial terms" (p. 14).

Ultimately, metacognition requires students to "externalize mental events" (Bransford, Brownish, & Cocking, p. 67), such as what it ways to learn, awareness of one's strengths and weaknesses with specific skills or in a given learning context, plan what'due south required to achieve a specific learning goal or action, identifying and correcting errors, and preparing alee for learning processes.

————————

1 Students who were tested with short answer in addition to multiple-choice questions on their exams reported more cognitively agile behaviors than those tested with merely multiple-option questions, and these active behaviors led to improved operation on the final exam.

References

- Adams, Maurianne, Bell, Lee Ann, and Griffin, Pat. (1997). Teaching for multifariousness and social justice: A sourcebook . New York: Routledge.

- Bransford, John D., Brown Ann L., and Cocking Rodney R. (2000). How people larn: Brain, heed, experience, and school . Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

- Baker, Linda, and Brown, Ann Fifty. (1984). Metacognitive skills and reading. In Paul David Pearson, Michael L. Kamil, Rebecca Barr, & Peter Mosenthal (Eds.), Handbook of inquiry in reading: Volume III (pp. 353–395). New York: Longman.

- Brown, Ann L. (1980). Metacognitive evolution and reading. In Rand J. Spiro, Bertram C. Bruce, and William F. Brewer, (Eds.), Theoretical issues in reading comprehension: Perspectives from cognitive psychology, linguistics, bogus intelligence, and education (pp. 453-482). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Chick, Nancy, Karis, Terri, and Kernahan, Cyndi. (2009). Learning from their own learning: how metacognitive and meta-affective reflections heighten learning in race-related courses . International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, iii(1). ane-28.

- Commander, Nannette Evans, and Valeri-Aureate, Marie. (2001). The learning portfolio: A valuable tool for increasing metacognitive awareness. The Learning Assistance Review, 6 (2), five-eighteen.

- Concepción, David. (2004). Reading philosophy with background knowledge and metacognition. Teaching Philosophy , 27 (four). 351-368.

- Dunning, David, Johnson, Kerri, Ehrlinger, Joyce, and Kruger, Justin. (2003) Why people fail to recognize their own incompetence. Electric current Directions in Psychological Science, 12 (3). 83-87.

- Flavell, John H. (1985). Cognitive development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Hatano, Giyoo and Inagaki, Kayoko. (1986). Two courses of expertise. In Harold Stevenson, Azuma, Horishi, and Hakuta, Kinji (Eds.), Child evolution and education in Japan, New York: W.H. Freeman.

- Helms, Janet E. (1995). An update of Helms' white and people of colour racial identity models. In J.G. Ponterotto, Joseph G., Casas, Manuel, Suzuki, Lisa A., and Alexander, Charlene Yard. (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural counseling (pp. 181-198) . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Lovett, Marsha C. (2013). Make exams worth more than the grade. In Matthew Kaplan, Naomi Silver, Danielle LaVague-Manty, and Deborah Meizlish (Eds.), Using reflection and metacognition to improve student learning: Across the disciplines, across the academy . Sterling, VA: Stylus.

- Palincsar, Annemarie Sullivan, and Brown, Ann Fifty. (1984). Reciprocal teaching of comprehension-fostering and comprehension-monitoring activities. Cognition and Instruction, 1 (2). 117-175.

- Pintrich, Paul R. (2002). The Role of metacognitive knowledge in learning, teaching, and assessing. Theory into Practice, 41 (4). 219-225.

- Salvatori, Mariolina Rizzi, and Donahue, Patricia. (2004). The Elements (and pleasures) of difficulty . New York: Pearson-Longman.

- Scardamalia, Marlene, Bereiter, Carl, and Steinbach, Rosanne. (1984). Teachability of reflective processes in written composition. Cerebral Scientific discipline , viii, 173-190.

- Schoenfeld, Alan H. (1991). On mathematics as sense making: An informal assault on the fortunate divorce of formal and informal mathematics. In James F. Voss, David N. Perkins, and Judith W. Segal (Eds.), Informal reasoning and education (pp. 311-344). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Stanger-Hall, Kathrin F. (2012). Multiple-option exams: An obstruction for higher-level thinking in introductory science classes. Prison cell Biology Instruction—Life Sciences Education, 11(3), 294-306.

- Tanner, Kimberly D. (2012). Promoting student metacognition. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 11, 113-120.

- Weimer, Maryellen. (2012, November nineteen). Deep learning vs. surface learning: Getting students to understand the difference. Retrieved from the Didactics Professor Blog from http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-professor-blog/deep-learning-vs-surface-learning-getting-students-to-understand-the-difference/.

- Zohar, Anat, and David, Adi Ben. (2009). Paving a clear path in a thick forest: a conceptual analysis of a metacognitive component. Metacognition Learning , iv , 177-195.

This teaching guide is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

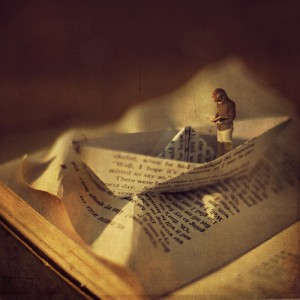

Photograph credit: wittygrittyinvisiblegirl via Compfight cc

Photo Credit: Helga Weber via Compfight cc

Photo Credit: fiddle oak via Compfight cc

How Was Value Added To Your Learning Process By Participating In The Metacognitive Forums,

Source: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/metacognition/

Posted by: bergergaceaddly.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Was Value Added To Your Learning Process By Participating In The Metacognitive Forums"

Post a Comment